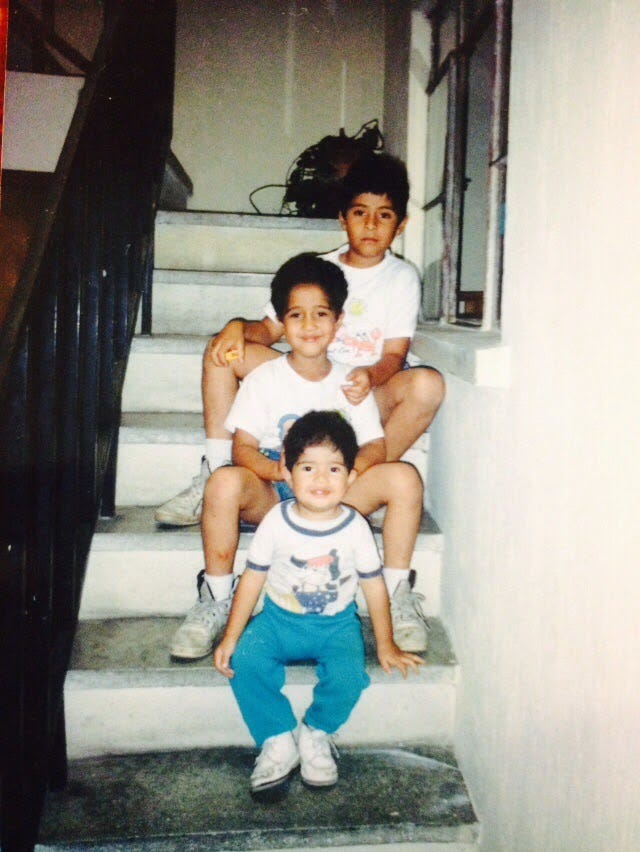

Writing and sharing about the relationship between my brother and I helped me realize that there are things about family that impact us all. As I have mentioned somewhere else, A Human Catechism is a family affair.1 As a family affair, it implies that there is beauty and affliction intertwined in the way we relate to each other. For that reason, I want to take the time to articulate five things I have learned that are helping me heal from my family system and understand family as something that transcends our nuclear family.

Firstly, It is important to acknowledge that the idea of the nuclear family was a construction of the 1950’s-60’s in the United States.2 Interestingly, this concept came to Latin America with the arrival of missionaries who shared the gospel of the American Dream. During my years in seminary, I took a class called “The Christian Family.” The course was designed to present the biblical idea of what the family is supposed to be. The interpretation of the family we learned goes like this: the family sprouts from the marriage between a man and a woman, who later procreate children. They are supposed to commit themselves to God and follow God’s law in raising children who will follow God and serve in the church, while also being productive to society. Little did I know, the professor was conveying an idea of the family that is not found in the Bible. The Bible presents the idea of an extended family. It also portrays the stories of broken families, violent patriarchs, and abused women and children. There are no good examples in the families of the Bible. The Bible presents the raw narrative of humans who perpetrate violence and experience suffering as they try to understand who God is amid their violence and trauma.

Some people may be tempted to say that this is because of the fall, sin, or whatever theological justification we want to use. Sin, however, is not a moral failure per se. It is a relational issue first and foremost, a rivalistic way to relate with one another. The reality is that our brokenness is the result of our rivalries and misplaced desires, which lead people to hurt each other.

Secondly, our families are the place where we learn to desire. It is within this imperfect web of relationships that we imitate who we become later in life. In other words, our families teach us how to engage in relationships outside of the family unit. We mimic not only our parents but also our sibling figures, and that sets the stage for both positive and negative ways of relating to each other. When learning from our immediate “blood” relatives, “siblings play a critical role in mimetic rivalries that characterize the family romance. As a consequence, our relations with siblings anticipate, for better or worse, later adult relationships. As we grow and our world expands beyond the immediate family to encompass other relationships, we may remain caught in rivalries that have characterized our initial relationship with siblings. Or, diverging from that scenario, we may experience with our siblings and with others a supportive intimacy that enables us to overcome the effects of trauma and violence in our life.”3 That is to say that our family of origin is the most important and longest-lasting influence in who we are.

The first two lessons have helped me to understand the third one. The way I show up in my faith community is directly related to the role I play(ed) in my family of origin. That is why it is so important that people take the time to heal from family trauma and grief. For example, I have noticed that I interact with other followers of Jesus in a way that resembles my family dynamics. I have also noticed that if people were submissive at home, it is very likely they will be submissive at church. If people grew up in a violent family and do not do the work to heal, they will transmit their suffering and pain on to others within their faith communities.4

Fourth, Giving voice to and dealing with suffering, trauma, and broken relationships is the only way in which we can transform our pain. As life happens and people grow old, it is important that pain and suffering are brought to the surface, for lament is the poetry of truth telling.5 It is important that our lamentation is not trying to blame those who have hurt us. That is why all of this ought to happen in the context of an extended family and web of relationships. We need family—some times it is a chosen family not a blood one—to walk alongside one another to tell the truth of our pain and integrate the fragments of our stories. We need the supportive intimacy that will give us the space to transform the violence and trauma of our life. Re-integrating the self is one way to experience the life-giving process of forgiveness. For that reason, I have come to believe that forgiveness is not forgetting, but remembering without resentment.

Finally, If there is no “model!” or “ideal” family, I am free to make up my own family. That is to say that blood is not what defines who is family. It is much more than our blood relatives. Friends, elders of our community, and mentor figures are part of our families. As a result, families have the potential to be an extended web of relationships that love, care, and support who people become and the way they show up in the world. That is why one of the things I am working on is building a solid web of relationships I can leave behind for my daughters. This relational fabric is not bounded by blood, but by values, care, genuine interest in each other’s life, and the desire to see a world where everybody can flourish. My hope is that this network is not the only thing I give to them. I also want to help them build the capacity and resources for them to weave their own relational tapestry.

These lessons have helped me heal. They are making the way for a new understanding of what family is. They are also opening my heart to others who may become family in the future.

Aguilar Ramírez, Joel David. A Human Catechism: A Journey from Violence and Collective Woundedness to Peacebuilding. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2024.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/03/the-nuclear-family-was-a-mistake/605536/

Reineke, Martha J. Intimate Domain: Desire, Trauma, and Mimetic Theory. East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 2014.

https://cac.org/daily-meditations/transforming-our-pain-2020-09-18/

O’Connor, Kathleen M. Lamentations and the Tears of the World. New York: Orbis Books, 2003.

I enjoyed reading this article a lot. To see you write in a such a way that makes sense to me about complex human relationships has helped me a lot. The line “forgiveness is not forgetting, but remembering without resentment. “ is something I have been thinking about ever since I first read it. It going along with broken relationships and healing from them is something I wanted to think about and that line has helped me focused that healing. Thank you Joel.

Your note on sin is especially transformative, I think. If sin is a moral failure, it's *because of* how it affects our relationships with others and our treatment of them. There is no morality in a vacuum; it's all relational.

I'm gonna be chewing for a while too on how my family experience affects the way I show up in my faith community. Most of that influence has been good, but since having my own kids I've also had to reckon with the maladaptive, overcompensating parts of my family system of origin and recognize/adapt/outgrow those things for the sake of my own home. I hadn't yet thought about how that work would extend into my church, but I'm glad to be thinking about it now...