I recently came back from a trip to the region of Ixcán in Guatemala. This is a very remote place that experienced some of the worst of the Guatemalan war. I was there to deliver a class on contextual Bible reading and theology to some local pastors and church leaders. For the last couple of weeks I have shared stories, reflections, and the theological insights that I learned through my experience there, for the pastors and leaders were my teachers, not the other way around. You can find the first three deliveries of this series below.

The account today is about our experience in reading the story of David and Bathsheba, in 2 Samuel 11. If you don’t know the story, I encourage you to read it before proceeding.

It is the second day of classes. I am tired and dehydrated. The heat and humidity are getting the best of me. My companions and I arrive at the church where we hold the classes. As we get out of the car, my friend Jaime tells me: “the pastors are very happy with what you did yesterday. We received messages during the night from a few of them telling us that they are re-thinking the way they pastor their churches.” The Spirit is at work. I know this is not because of me. I am so tired! I have never been this tired while teaching.

My guess is that the emotional charge of the place, history, and stories of the pastors and church leaders, the context, is hitting my body like a ton of bricks. I remember what Gena St. David says: “some stressful events are chronic, like systemic poverty, war, or long-term child abuse or neglect.” I am in the face and space of systemic and continuous trauma. No wonder why my body is reacting so strongly. I know Gena would say that I need to allow myself to feel what is going on.1

The exercise in contextual Bible reading today is around the story of Bathsheba. The lesson actually says that I am supposed to be teaching about David. However, the story of David would be nothing without one of the grandmothers of Christmas.

As we read the text, I remind the students that one of our commitments is to read The Bible critically. In other words, we have to constantly as the question “why?”2 We are all in agreement, and we begin by identifying the characters of the story. David, Bathsheba, and Uriah, are the three main characters, and the narration of the story and dialogue immediately sparks the interest and curiosity of the class participants.

After a few minutes of conversation, one of the pastors asks a question that I find quite interesting: “Why didn’t Bathsheba take better care of herself? Why would she tempt King David?” I am ready to respond. I feel the temptation of correcting his reading. However, our conversation takes an unexpected turn when another pastor interjects and says: “She was in her house, alone. Why was David looking down from his terrace?” He is reading critically. He is asking why. Another student interrupts him and asks, “doesn’t the text say she was taken? She couldn’t say no, it was the King’s messengers who took her.” Without my help the text is leading them away from idealizing David. The Spirit is moving. I just need to sit back and listen.

For the next thirty minutes we talk about rape, sexual abuse, and the abuse of power by Bible characters. We extrapolate the discussion to contemporary political and church leaders. The pastors seem very uncomfortable. They don’t know what to do with the conversation. All of a sudden, one of the students, a pastor who leads a small congregation of about forty five people raises his hand. I stop whatever I am saying and open the space for him to share. “I don’t know how to say this. There are many young women in my congregation who are constantly approaching me,” He says. At this point, my mind is racing and I am fearing that he will try to justify possible abuse in his congregation. But, he surprises me. I am judging prematurely. He further explains, “These women come to me crying. I am afraid, pastor. They say. My uncle gets in my bed at night. My father is molesting me, pastor. They are threatening me, pastor. They all say stuff like that!” Everybody is listening attentively to him. Then he continues, “How do I pastor them? What do I say? I tell them to go to the police. But, where are they going to go? They have to put up with their abuse and suffer through it because they have nowhere to go.” He finishes by saying, “At least I know now that the Bible tells stories about what they go through.” There is no consolation in his voice, just the truth as it is.

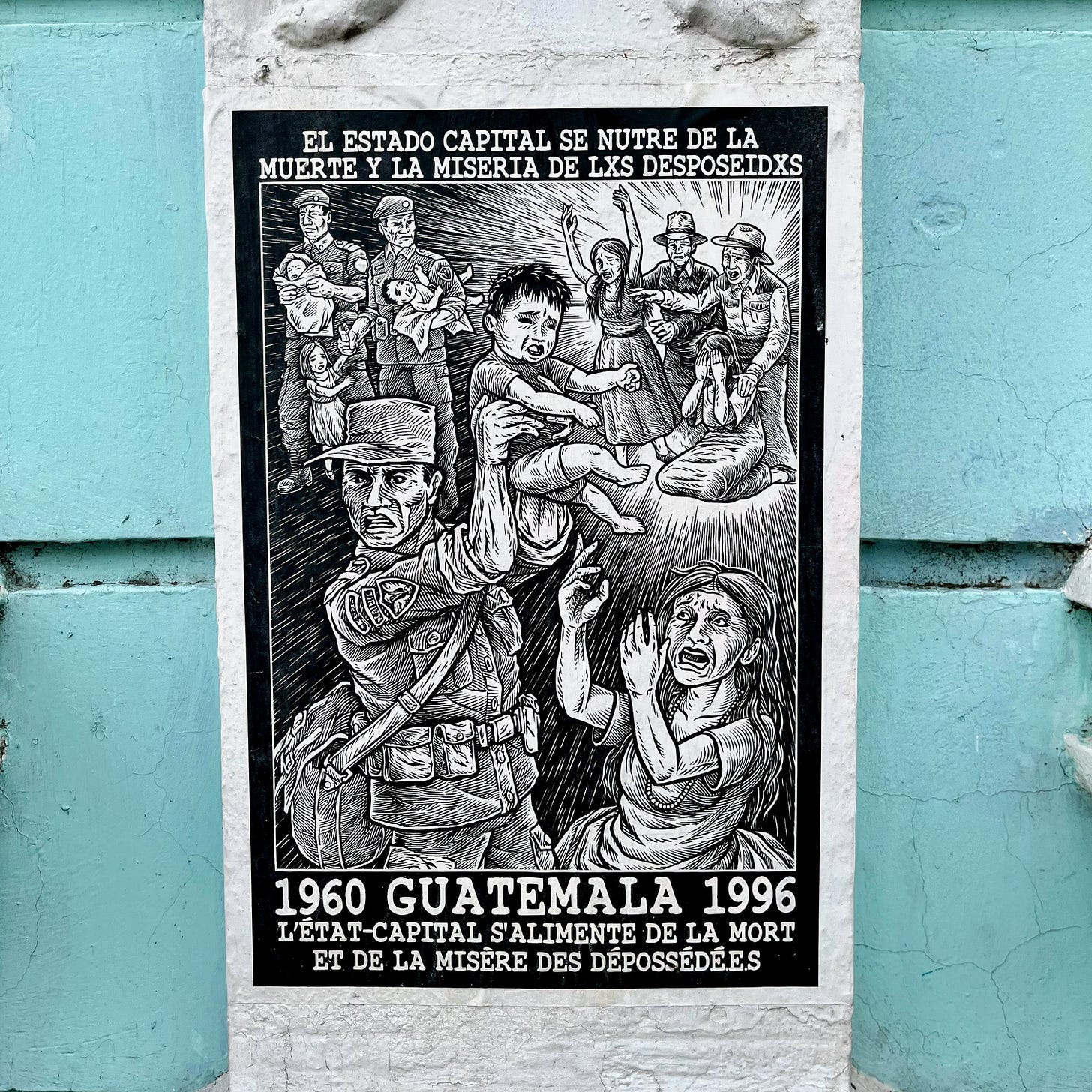

My heart is aching at this point. I have nothing to say to him. I wish I had an answer. The history of their land and communities is one of war and sexual violence. The Guatemalan war has countless testimonies of sexual violence against women and little girls. Raping and sexual slavery were used to sow fear and terror in the civilian population.

Later on, one of the leaders who is putting together this training explains to me that sexual abuse runs rampant in the communities around Ixcán. It is the legacy of the war. Men who fought the war still perpetrate sexual violence in their communities. People know who they are and what they are capable of. For that reason, they all stay silent.

I am struggling to see redemption in what happened in class today. It feels as if the Spirit is at work. However, after this interaction, I am struggling to see Her movement. The Bible verses we use as band-aid theologies cannot contain the bleeding. No, not all things work for the good of those who suffer violence of any kind, not even for those who love God. I can’t do more than just sit with the pastors and mourn with them as they open their hearts to a different way to read The Bible. We stay silent, bring the conversation to a close, and go to our coffee break.

St. David, Gena. The Brain and The Spirit: Unlocking the Transformative Potential of the Story of Christ. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, 2021. p. 168

West, Gerald O. “Reading the Bible with the Marginalised : The Value/s of Contextual Bible Reading.” Stellenbosch Theological Journal 1, no. 2 (2015): 235–61. https://doi.org/10.17570/stj.2015.v1n2.a11.

I have loved this series so much . Thankyou

This is a difficult situation. My first instinct would be to make a safe place for victims to go being careful not to promote putting their safety in any organisation of the flesh. The Scriptures are clear though, we cannot send them on their way saying, "be warmed and be filled". It takes a community to stand up to sexual predators and hold them accountable, refusing to do trade or have anything to do with them. I suspect you're dealing with wounds of sexism as well as many of these men will be patriarchs in their homes and communities. Denying them these roles pulls at the very fabric of their world and rumours of power. The temptation to answer violence with violence is strong when it comes to sexual abuse.

One thing is certain, they ought be removed from the situation to a safe and dedicated place, and cared for by the fellowship until they can provide for themselves. The people should then be equipped with a response plan when sexual violence affects their community which will likely take a reintegration of the Anthrohead to include the body as central to redemption. All of this, of course, within their context--each step may well take years to implement. The slow work of the gospel can be supplemented with swift action to free those caught in sexual slavery to their abusers.